¿Qué pasa si se aprueba una ley pero nadie la hace cumplir? Eso es básicamente lo que ha ocurrido con una pequeña pero útil normativa sobre los hospitales y la asistencia financiera para cubrir facturas médicas.

La Ley de Cuidado de Salud a Bajo Precio (ACA), también conocida como Obamacare, requiere que los hospitales sin fines de lucro pongan a disposición de los pacientes de bajos ingresos asistencia financiera, y que publiquen esas políticas en línea.

En los Estados Unidos, más de la mitad de los hospitales son sin fines de lucro, y en algunos estados todos o casi todos los hospitales lo son. Pero muchas personas que califican para recibir asistencia financiera —o “atención caritativa”, como también se la llama— nunca la solicitan.

Jared Walker está ayudando a correr la voz. Ha fundado Dollar For, una organización que ayuda directamente a las personas a utilizar las normas de asistencia financiera de los hospitales para hacer frente a las facturas médicas imposibles de pagar. Walker se ganó la atención del público a principios de este año a través de un TikTok viral que hizo una noche de manera informal.

En el video, de 60 segundos, Walker expone los aspectos básicos de la solicitud de asistencia financiera hospitalaria, en respuesta a un aviso que le pide a los TikTokers compartir “algo que hayas aprendido y que pareciera ilegal saber”.

“La mayoría de los hospitales de los Estados Unidos no tienen ánimo de lucro, lo que significa que deben tener políticas de asistencia financiera o de atención caritativa”, dice en el video. “Esto va a sonar raro, pero lo que esto significa es que si ganas menos de cierta cantidad de dinero el hospital tiene la obligación legal de perdonar tus facturas médicas”.

En el video se explican los fundamentos de la solicitud de atención caritativa en los hospitales, y eso es lo que él dice que utiliza para “erradicar” las facturas médicas.

“An Arm and a Leg”, un podcast sobre el costo de la atención médica, ha estado cubriendo el trabajo de la asociación de Walker desde que el video se convirtió en viral, así como la batalla de décadas por establecer las reglas de caridad.

Las siguientes son cinco estrategias que Walker comparte durante las sesiones mensuales de formación de voluntarios:

1. ¿Cómo encontrar estas normas?

El truco de Walker para encontrar la política de asistencia financiera de un hospital es muy sencillo: búscalo en Google. Escribe el nombre del hospital, seguido de “política de asistencia financiera” o “política de atención caritativa”. Los primeros resultados de la búsqueda serán probablemente un resumen de la política y una aplicación.

Tu primera intención puede ser ir a la página principal del hospital. Pero probablemente sea un error. Según Walker, estas normas suelen estar ocultas en los menús de los sitios web de los hospitales. En muchos estados, las leyes de atención caritativa son más específicas que lo que se indica en ACA, y los hospitales pueden estar obligados a destacarlas de manera prominente.

Es raro que estas normas no estén disponibles en línea en absoluto, pero en algunos casos, dijo Walker, puede que tengas que llamar al hospital y pedirles una solicitud.

2. ¿Quién califica?

La mayoría de las políticas de atención caritativa de los hospitales se basan en los ingresos, utilizando porcentajes de las directrices federales de pobreza para definir la elegibilidad. En un ejemplo, Walker mostró las directrices del Hospital St. Luke’s de Kansas City, donde los pacientes que ganan el 200% de los niveles federales de pobreza son responsables del 0% de su factura. Esa cifra era de poco más de $2,000 al mes en 2021. Aquellos que ganan entre el 201% y el 300% eran elegibles para ciertos descuentos.

¿No tienes claro cómo se comparan tus ingresos con los niveles federales de pobreza? Hay calculadoras en internet que te ayudarán. Recuerda que tu hogar eres tú, más tu cónyuge, y cualquier persona que declares como dependiente en tus impuestos. Quienes comparten la vivienda no cuentan.

Las solicitudes suelen requerir documentación que demuestre tus ingresos. Los hospitales piden cosas como talones de pago recientes, prueba de desempleo, cartas de concesión de la Seguridad Social y declaraciones de impuestos, según Walker. Los documentos exactos que puede pedir el hospital pueden variar. Pero un hospital no puede negarte la ayuda por no proporcionar un documento que no se especifica en la solicitud.

3. ¿Presionado por los pagos? Todavía puedes tener tiempo

El IRS exige a los hospitales sin fines de lucro que den a los pacientes un período de gracia de 240 días (unos ocho meses), a partir de la fecha de facturación inicial, para solicitar asistencia financiera. Pero los hospitales están autorizados a enviar las facturas a las agencias de cobro mucho antes, a menudo después de sólo 120 días.

En ese momento, los pacientes suelen sentirse acosados por las notificaciones de las agencias de cobro. Aun así, les pueden quedar meses para solicitar asistencia financiera, y avisar a las agencias de que se está tramitando una solicitud con el hospital puede, a veces, frenar el envío de cartas.

“El hospital puede sacarte de los cobros con la misma facilidad con la que te mete en ellos”, afirmó Walker.

En algunos casos, los hospitales perdonan las facturas que tienen más de 240 días. E incluso de varios años atrás, dijo Walker. No está de más pedir ayuda.

4. ¿Parece que no vas a calificar? Escribe una carta

Si no cumples los requisitos basados únicamente en los ingresos, pero sigues sin poder pagar las facturas del hospital, no te desanimes. Lo mismo ocurre si la política de ayuda financiera del hospital especifica que sólo pueden calificar las personas no aseguradas; es posible que tengas un seguro, pero que aun así te encuentres con facturas gigantescas que no puedes pagar.

Walker aseguró que mandar una carta explicando las dificultades financieras junto con la solicitud puede ser de gran ayuda. De hecho, anima a todos los pacientes a que adjunten una carta, aunque su solicitud parezca sólida.

“Hay otros seres humanos que las leen y las cartas son de gran ayuda”, dijo. En última instancia, cada hospital decide quién recibe la asistencia que está legalmente obligado a proporcionar. Presenta tu caso.

5. Sí, es posible que tengas que enviarla por fax

Aunque muchos hospitales disponen de portales digitales que permiten pagar las facturas en línea, no suele haber un equivalente para solicitar asistencia financiera. Muchas solicitudes sólo ofrecen una dirección postal. Pero Walker y su equipo han comprobado que las solicitudes enviadas por correo se pierden con frecuencia.

En su lugar, recomiendan llevar la solicitud al hospital y entregarla en mano o enviarla por fax. Las bibliotecas públicas, los locales de FedEx y ciertos servicios en línea hacen posible el envío por fax incluso si, como la mayoría de la gente, no ha utilizado un aparato de fax desde finales de los años 90.

Cuando se trata de acceder a la atención benéfica, “vas a tener que pasar por saltar un montón barreras”, señaló Walker, “pero vale la pena”.

Emily Pisacreta es reportera y productora de “An Arm and a Leg”, un podcast sobre el costo de la atención sanitaria que es coproducido con KHN.

Related Topics

Contact Us

Submit a Story Tip

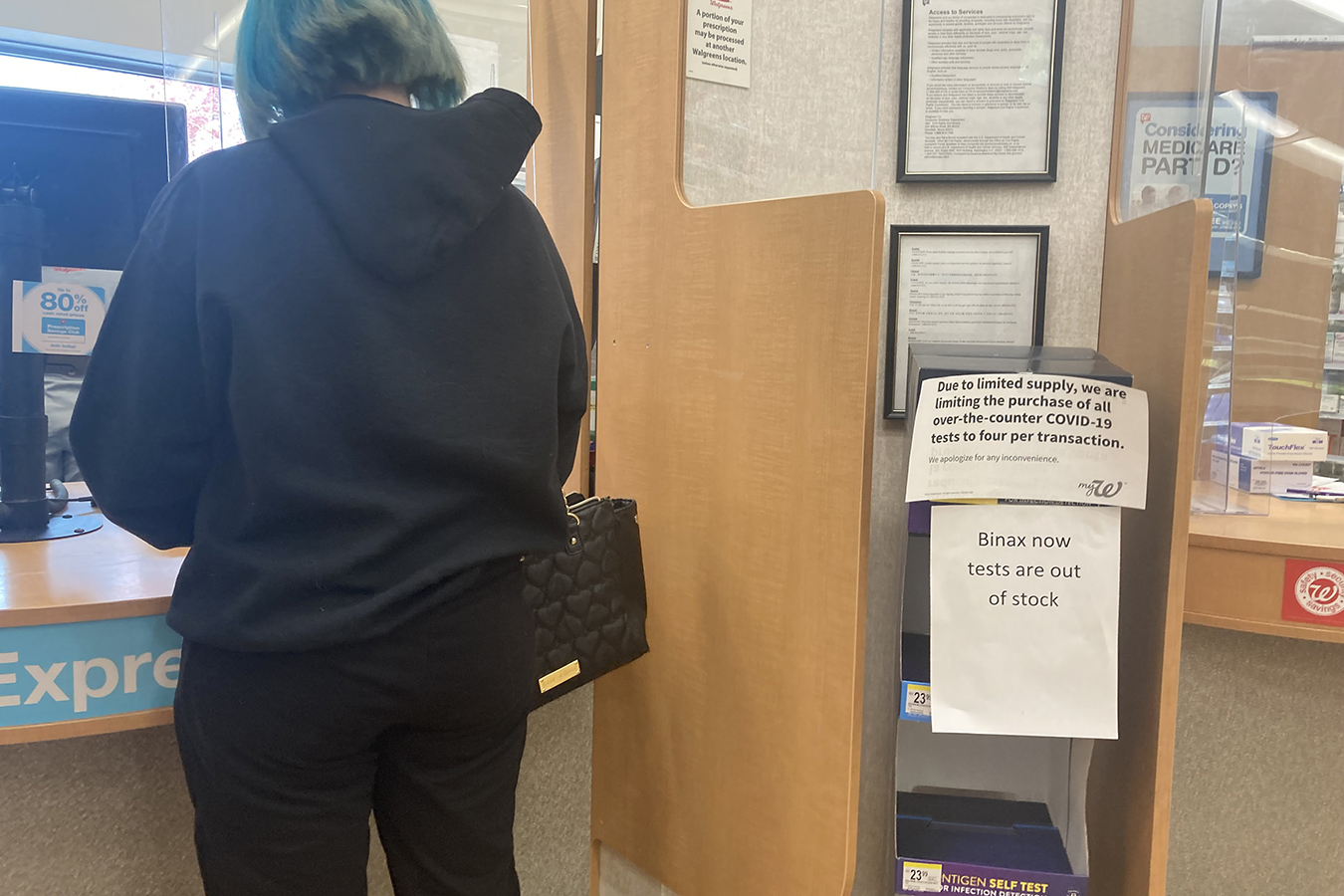

Un cartel alerta a los consumidores en una farmacia Walgreens en Helena, Montana, el 5 de octubre de 2021, que las ventas del test casero para covid-19 están racionadas.

Un cartel alerta a los consumidores en una farmacia Walgreens en Helena, Montana, el 5 de octubre de 2021, que las ventas del test casero para covid-19 están racionadas.

Susan Goodlaxson of Baltimore says she repeatedly called the city asking for curb cuts and sidewalk repairs. She remembers a crew coming to look at the sidewalks, but nothing happened.

Susan Goodlaxson of Baltimore says she repeatedly called the city asking for curb cuts and sidewalk repairs. She remembers a crew coming to look at the sidewalks, but nothing happened. A trip to the library for Baltimore’s Susan Goodlaxson, who uses an electric wheelchair, would require riding in the street to avoid rampless curbs and broken sidewalks. “I don’t feel like it’s asking too much to be able to move your wheelchair around the city,” Goodlaxson says.

A trip to the library for Baltimore’s Susan Goodlaxson, who uses an electric wheelchair, would require riding in the street to avoid rampless curbs and broken sidewalks. “I don’t feel like it’s asking too much to be able to move your wheelchair around the city,” Goodlaxson says.