By Dr. Frank A. Blazich Jr., Historian, U.S. Navy Seabee Museum

William P.S. Sanger served the U.S. Navy for over half a century as both a civilian and an officer. As the first commissioned Civil Engineer Corps (CEC) officer, and the first civil engineer for the Bureau of Navy Yards and Docks (BuDocks), Sanger witnessed the transformation of the role and importance of civil engineers and the Navy shore establishment.[i]

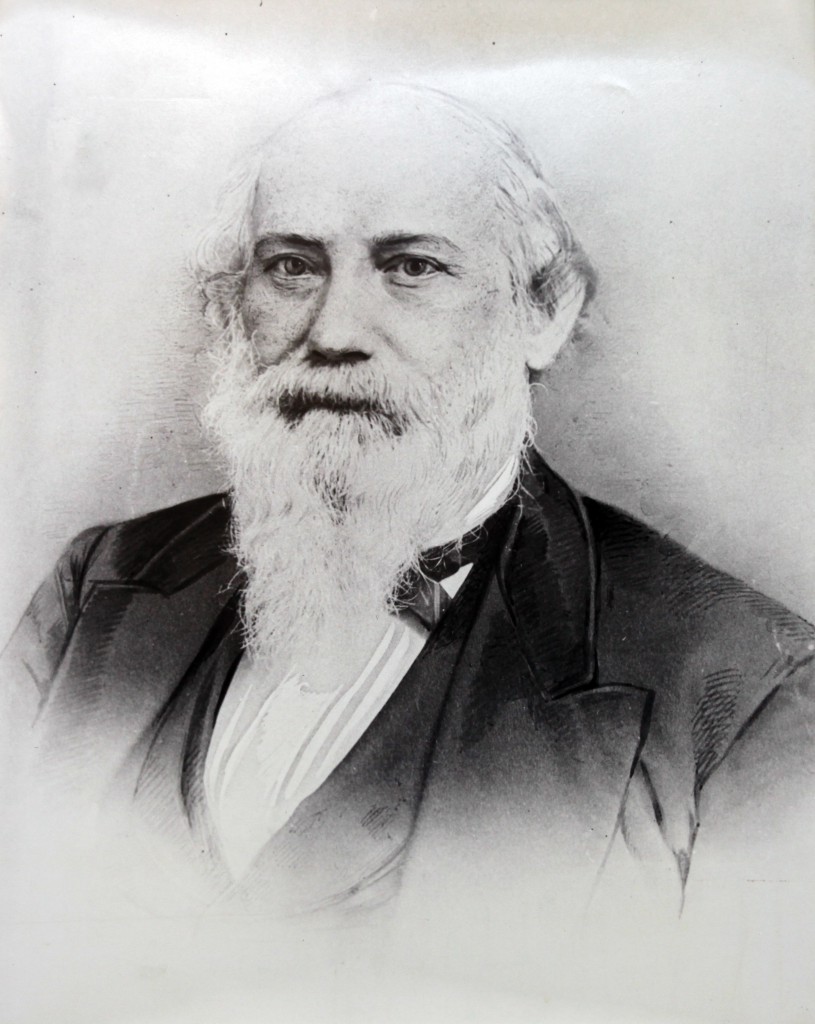

Capt. William P.S. Sanger, CEC, USN, c. 1870s. (Source: U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Naval Base Ventura County, Port Hueneme, California)

Unfortunately, little is known of the early years of Sanger’s life. On May 26, 1810, William was born to Samuel Sanger and Mary Hart of Ward 10 in Boston, Massachusetts. Samuel was the son of a seafarer, Capt. Samuel Sanger Sr., and served as the city health commissioner for Ward 10.[ii] William presumably continued to live with his parents during this time, possibly assisting his father with his work.[iii]

On May 24, 1824, days before Sanger’s 14th birthday, Massachusetts Sen. James Lloyd submitted a resolution requesting that the Secretary of the Navy provide information to the Senate “relative to the expediency of constructing, at one of the navy yards of the United States, a dry dock … and to report on the usefulness, economy, and necessity, of a dry dock; the best location therefore, and the probable expense of construction of such dry dock. …”[iv] The resolution was agreed upon by the Senate. Navy Secretary Samuel L. Southard responded in January 1825 and recommended construction of two dry docks, one at Charlestown (Boston), Massachusetts, and the other at Gosport (Norfolk), Virginia, at an estimated cost of $700,000, as calculated by Colonel Loammi Baldwin.[v]

Plans for the dry docks materialized in 1826. On May 8, 1826, Congress resolved that President John Quincy Adams task engineers to examine and survey sites for dry docks at the navy yards of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Charlestown, Massachusetts, Brooklyn, New York, and Gosport, Virginia. On July 26, the Navy Department appointed Baldwin to conduct the necessary surveys.[vi] He submitted his examinations and surveys to the Navy on Dec. 28, 1826, and Southard thereafter recommended to Adams that, funds permitting, the docks be constructed in order of descending priority at Charlestown, Gosport, Brooklyn and Portsmouth.[vii] After reviewing Baldwin’s work and the Navy’s assessment, on March 3, 1827, Congress authorized the president to construct dry docks at Charlestown and Gosport.[viii]

After Congressional approval, the Navy swiftly requested and secured Baldwin’s agreement to serve as the superintendent engineer for the dry docks’ construction in March 1827.[ix] At some point from spring to summer 1827, the 17-year old Sanger entered into an apprenticeship with Baldwin, the exact circumstances of which remain hazy.[x] Samuel Sanger’s work as a health commissioner may have positioned him to contact Baldwin, either directly or through a mutual acquaintance, to try and find William a suitable profession. Civil engineering in the early 19th century followed a pattern established in Europe. There were no formal academic programs in the United States in the 1820s. The first civil engineering degrees were awarded by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, but not until 1835.[xi] Sanger would have paid a premium, approximately $200 a year for two years of apprenticeship, while collecting some compensation from field work.[xii] In addition to having available financial resources, Sanger clearly demonstrated education and aptitude worthy of Baldwin’s stature to accept him as an apprentice. In 1826, he graduated from English High School in Boston, being named a Franklin Medal Scholar for meritorious scholarship for finishing at or near the top of his senior class.[xiii] In regards to the timing of the apprenticeship, in July 1827 Baldwin wrote to William Strickland, an accomplished Philadelphia architect, and inquired about “the terms upon which young men are taken as pupils in the profession of Engineers.”[xiv] Perhaps Baldwin needed advice in the apprenticing of Sanger, but this is only conjecture.

Construction of the dry dock at Charlestown began in June. Capt. Alexander Parris, a talented architect-engineer from Massachusetts, served as the Charlestown project’s assistant superintendent, accompanying Baldwin on his surveys and inspections of the work.[xv] Parris’ association with the Charlestown Navy Yard dated back to the spring of 1824, when he prepared plans for a wall at the yard paralleling the Salem Turnpike.[xvi] With work underway in Charlestown, on September 8, 1827 Baldwin wrote Tobias Watkins, the fourth auditor of the U.S. Treasury, regarding his finances. The engineer noted that additional commitments requested by the Navy Board of Commissioners for surveying and drawing of plans obliged him “to employ others to assist in this department. …”[xvii] When work in Gosport began in November, Sanger served as Baldwin’s resident engineer.[xviii] It is thus postulated that Sanger began his civil engineer apprenticeship under Baldwin between March and November 1827, with his work centered on Gosport, accompanying Baldwin on occasion. Parris served as Baldwin’s main assistant, and joined the engineer during his visits at both dry docks during the period of their construction.[xix]

Sanger worked under Baldwin until completion of the Gosport dry dock in 1833. He assisted in surveys of the yard and waters before continuing as resident engineer overseeing the actual construction.[xx] Baldwin lost his notebooks recording the work on the dry docks when the steamboat William Penn ran aground on the Delaware River and burned near Philadelphia on March 4, 1834, so exact details of Sanger’s work remain nebulous.[xxi] On June 17, 1833, the dry dock opened to admit the USS Delaware, the first vessel ever to enter an American dry dock. Less than a year later, the dry dock was turned over to the yard’s commandant on March 15, 1834, and was built at a total cost of $974,356.65.[xxii]

The day of careening vessels to repair them ended at Gosport June 17, 1833 when sailors powering a capstan slowly drew the 74-gun Delaware into Drydock 1. Designed by a famed civil engineer, Colonel Loammi Baldwin, the dry dock could then host the nation’s largest ships. Thousands of excited spectators watched as a powerful steam engine pumped the dock dry. (Source: Naval History and Heritage Command)

The day of careening vessels to repair them ended at Gosport June 17, 1833 when sailors powering a capstan slowly drew the 74-gun Delaware into Drydock 1. Designed by a famed civil engineer, Colonel Loammi Baldwin, the dry dock could then host the nation’s largest ships. Thousands of excited spectators watched as a powerful steam engine pumped the dock dry. (Source: Naval History and Heritage Command)

Following completion of the dry dock, Sanger remained in Norfolk. In the late summer and early fall of 1833, he surveyed the area between Great Bridge in Norfolk County and North Landing in Princess Anne County for the purpose of determining the cost of building a canal for the Virginia Board of Public Works.[xxiii] He wrote to Baldwin in May 1834 regarding leaks in the docks at the Navy Yard, and suggested that his mentor be named the yard’s engineer.[xxiv] Instead, with his apprenticeship complete, Sanger remained at Gosport and became civil engineer for the yard. Serving essentially as a public works officer for the yard’s commandant, Commodore Lewis Warrington, he improved facilities at the yard, oversaw completion of a smithery, iron store, timber sheds, mast shop, boat shop, commandant’s house and assorted other structures.[xxv] On February 20, 1834, Sanger married Martha Webb in Norfolk, Virginia.[xxvi] He continued his work at the yard until July 8, 1836, when the Board of Navy Commissioners employed him as a civil engineer.[xxvii]

The reason for this employment is not entirely clear, but it appears to once more involve Baldwin. In June 1836, Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson wrote Baldwin to request a survey for the practicality of establishing a navy yard either near Great Barn Island, Perth Amboy, or Jersey City in New York and New Jersey. In his report of October 17, 1836, Baldwin remarks that he proceeded “after having obtained the necessary assistants” to survey the ground at the three locations. In a report of July 11, 1836, the Board of Navy Commissioners listed an additional clerk. Sanger, quite possibly, came into employment for the purpose of assisting Baldwin, who would be able to request his services.[xxviii] Whatever the case, Sanger’s employment by the board did not change his work at Gosport, as he continued to hold the position of civil engineer of the yard into 1842.[xxix]

Some of the first CEC officers (left to right): Benjamin F. Chandler, Franklin C. Prindle, William P.S. Sanger, Franklin A. Stratton, and Charles Hastings, c. 1870. (Source: U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Naval Base Ventura County, Port Hueneme, California)

Some of the first CEC officers (left to right): Benjamin F. Chandler, Franklin C. Prindle, William P.S. Sanger, Franklin A. Stratton, and Charles Hastings, c. 1870. (Source: U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Naval Base Ventura County, Port Hueneme, California)

The Establishment of BuDocs

The reorganization of the Navy and the creation of BuDocks would pave the way for Sanger to become the bureau’s first civil engineer. An expanding fleet, with requisite increasing duties, overtasked the Navy commissioners, and in 1839, the House of Representatives charged Navy Secretary James K. Paulding to devise a plan to reorganize the Navy under a bureau system. Paulding proposed a bureau to handle shore facilities, commanded by a line officer, with a staff including a civil engineer.[xxx] On August 31, 1842, President John Tyler signed the subsequent bill reorganizing the Navy into a series of five bureaus, including authorization for a civil engineer in the new Bureau of Navy Yards and Docks [xxxi] (now NAVFAC). Warrington, appointed as the first BuDocks chief, wrote to Sanger on September 7, 1842 and offered him appointment as civil engineer for the bureau. Sanger accepted the offer on the ninth, and on September 15, 1842, officially became the first civil engineer for BuDocks at an annual salary of $2,000.[xxxii]

Sanger’s duties as BuDocks civil engineer in the 1840s kept him busy managing the improvement and expansion of the Navy’s shore facilities. Among his body of work during the decade, he personally inspected the conditions of the yards at Portsmouth, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Gosport, Pensacola and Brooklyn. Commencing in the fall of 1843 and continuing into the next decade, Sanger either directly surveyed, oversaw construction of or reviewed plans for construction of new dry docks in New York and Pensacola, and for the establishment of a new navy yard in Memphis, Tennessee. He traveled to Memphis with a board of officers to select the site and draft a diagram of the future yard. Following this trip, he accompanied another board of officers to examine and report on the advantages of dry docks and floating docks at the harbors of Pensacola and Portsmouth, finishing this work in early 1845. Unfortunately, soil conditions at the New York dry dock and at the Memphis Navy Yard caused delays, cost overruns and headaches for Sanger and BuDocks.[xxxiii] Following Memphis, Sanger took over as chief engineer for construction of the stone dry dock at the New York Navy Yard in March 1845, remaining until February 1846 when he returned to BuDocks.[xxxiv] Problems aside, in 1850 Sanger and civil engineers at navy yards became part of the civil establishment, thereafter classified as civil officers in the federal government.[xxxv]

With the discovery of gold in California, westward expansion necessitated the establishment of a navy yard in the west. Completion of the New York dry dock in 1851 ended one area of concern for Sanger and ensured available dry dock facilities at all seven navy yards. Selection of a naval yard in California thereafter became the principle focus for the BuDocks engineer, notably after Congressional approval for a floating dry dock in that state in March 1851.[xxxvi] In early 1852, Sanger accompanied a naval commission, which traveled to the Golden State to survey and select a site for the new yard. Returning in August, the commission recommended Mare Island, 20 miles from San Francisco, as the desired location.[xxxvii] The Navy purchased the land in March 1853 and the yard began operations the next year.[xxxviii] A sectional floating dry dock, the object of Congress’ initial desire, was completed in 1855.[xxxix] Back east, the unstable soil and erosion issues at the Memphis Navy Yard inhibited further development, and Congress authorized the ceding of the yard and property to the city in 1854.[xl]

The work of Sanger and other civil engineers at the yards began to attract the attention of Navy Secretary James C. Dobbin. In 1853 in his annual report, Dobbin noted discord between sea and civil officers, and commented that he saw “no objection to the assignment of a proper rank to the civil officers of the Navy; not merely as a gratification of pride, but to prevent discord.”[xli] Two years later, he wrote that “After much reflection and attentive observation of the practical working of the present system, I am very favorably inclined to … establishing a distinct corps in the Navy, whose duty shall be confined to hydrography, ordnance, civil engineering, and other scientific duties.”[xlii] Dobbin’s ideas and views, however, did not stir Congress to action.

For the remainder of the decade, Sanger confined his travels to inspections or visits of navy yards along the East Coast. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, the navy yards predominantly expanded existing works, modernized with the introduction of gas light and enhancements in the area of steam propulsion, or repaired existing structures.[xliii] These projects required the services of additional civil engineers, and beginning in the late 1840s, Sanger began to hire men for the yards. By the outbreak of war in April 1861, the Portsmouth, Boston, New York, Norfolk, Pensacola and Mare Island Navy Yards all employed a civil engineer.[xliv] In 1858, Sanger prepared formal regulations defining the duties and responsibilities of the civil engineer at a navy yard as part of the proposed revised Code of Regulations for the Government of the Navy.[xlv]

Initially, the commencement of hostilities placed Sanger and BuDocks in a precarious situation. Prior to the outbreak of war, rebels captured the Pensacola Navy Yard with its floating dry dock on January 12, 1861.[xlvi] Even worse was the fall of the Norfolk Navy Yard in April 1862. On the 20th, Union forces abandoned and hurriedly attempted to destroy what they could at the yard in the face of Confederate forces. Over a thousand cannons, one of the nation’s finest dry docks, tools and facilities to construct and repair large warships fell into Confederate hands. Upon reaching the yard, the rebels found the dry dock undamaged and the scuttled hulls of the USS Merrimack, Germantown, Plymouth and Dolphin. The Merrimack would soon enter the dry dock in May, emerging as the ironclad CSS Virginia.[xlvii] Both yards would be thoroughly destroyed (and the Virginia blown up) by the Confederates on May 10, 1862 following the surrender of Norfolk, with orders to withdraw forces from the coast.[xlviii] In his annual report, BuDocks Chief Commodore Joseph Smith deemed the yards to be in states of ruin, fire having reduced buildings to mere masonry shells.[xlix]

The phoenix of a modern Navy rose from the ashes of Norfolk and Pensacola, one clad in iron. Sanger, however, was initially slow to grasp the technological shift and its impact on the shore establishment. The clash of the CSS Virginia and USS Monitor on March 9, 1862 demonstrated the advantages of this revolutionary class of warship, and henceforth yards had to adapt and transform for this new “iron age.” After the recapture of the ruined yards, from August to October 1862, Sanger served on a board to examine League Island in the Delaware River near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the harbor of New London, Connecticut, and the waters of Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, as sites for a new navy yard intended to build and support ironclads. Sanger personally surveyed the three areas, and together with the majority of the board recommended New London, with the minority in favor of League Island.[l] Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles agreed that New London possessed good qualities for a navy yard, “provided it be the intention of Congress to establish another similar to those we now have for the construction of wooden vessels.”[li] Welles rejected the conservative selection of New London and instead chose League Island for its characteristics conducive to ironclads.[lii]

But before ironclad or iron-hulled ships could dominate the waters, the war remained to be won. Repairs at Norfolk commenced in earnest beginning in late 1862, whereas work at Pensacola remained minimal, confined to only those buildings necessary to service vessels of the gulf squadron. Elsewhere the shore establishment expanded to meet exigencies from war, with temporary navy stations established at Ship Island, Mississippi; Memphis, Tennessee; Port Royal, South Carolina; Key West, Florida, and Mound City, Illinois.[liii] The latter three stations grew notably during the war as coaling stations and repair bases for the respective naval squadron in the area of operations.[liv] Despite the wartime growth, Welles deemed the nation’s navy yards “of limited area, and wholly insufficient for our present navy.”[lv] He advocated enlargement of the yards at Boston and New York, completion of Mare Island, rebuilding the destroyed yards, and building of a yard at League Island to handle iron and steam-powered vessels in an efficient manner.[lvi]

The First Civil Engineer Corps Officers

Meeting Welles’ expectations would necessitate increased resources. As with most postwar military budgets, fiscal resources shrank and navy yard operations were substantially reduced. Yards needed to be expanded for iron and steam facilities and shops and manage the larger fleet and ironclads.[lvii] All of this required competent civil engineers to manage the technical requirements amidst tight budgets. On February 20, 1867, Congress debated legislation to establish the offices of civil engineer and master mechanic in the navy yards via presidential appointment.[lviii] The intent of the bill was to ensure that the supervisory head of certain navy yard departments remained a trained, competent individual able to appoint or discharge personnel as required. Since line officers began to take command of such departments during the war, this removed men such as Sanger from exercising their supervisory role.[lix] On March 2, 1867, the legislation passed into law providing for Navy civil engineers to be appointed by the president, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.[lx]

Commissions came swiftly. Sanger received his as the first officer of the Civil Engineer Corps on March 3rd.[lxi] Weeks later on the 28th, Benjamin F. Chandler, Charles Hastings, Franklin A. Stratton and Wallace M. Spear received commissions as the next members of the CEC.[lxii] On July 15, 1870, civil engineers finally received pay fixed with that of other naval officers.[lxiii] The following year, Sanger and his fellow civil engineers received relative rank with officers of the line and precedence with officers of the line in accordance with their length of service.[lxiv] Unfortunately, the legislation did not clarify exactly how relative rank would be distributed or affixed to Sanger and his fellow CEC officers, at least not for any foreseeable future. The men received the title of “Civil Engineer,” with Sanger’s listed as “Chief Civil Engineer.”[lxv]

Limited appropriations for the naval shore establishment did not curtail the work of BuDocks. In February 1867, Congress authorized the Secretary of the Navy to accept League Island for development as a navy yard, and to dispose of the existing Philadelphia Navy Yard site.[lxvi] Work on this site began in earnest in 1871, and from 1872 to 1873, Sanger presided over a board to shape the future development of the yard.[lxvii] After completing this report, Sanger returned to Mare Island in September 1873 to head a board preparing plans to improve that yard.[lxviii] Elsewhere, the Naval Appropriations Act of 1868 authorized the gift of land from Connecticut for establishment of a naval station at New London, and work commenced in 1869 for what soon became a coaling station.[lxix] After his journey to Mare Island, Sanger apparently remained in Washington to oversee the CEC for BuDocks. A board of civil engineers assembled to plan improvements for the New London naval station in 1875 would be headed up by Chandler, and not Sanger.[lxx]

The year 1881 would leave the chief civil engineer a lasting legacy for the CEC and the Navy. Throughout the latter part of the 1870s, Congressmen had introduced numerous pieces of failed legislation to clarify the issue of relative rank for civil engineers.[lxxi] On February 24, 1881, however, Navy Secretary Nathan Goff Jr. issued General Order No. 263 conferring relative rank by presidential authority on CEC officers, with the relative rank of captain conferred on Sanger.[lxxii] In June, U.S. Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh established that Navy civil engineers were officers belonging to the Navy’s staff corps, entitled to be retired from active duty and placed on the retired list.[lxxiii] Thereafter on July 14, 1881, the Navy Department issued new regulations governing the appointment of civil engineers in the Navy, requiring future candidates to be between the ages of 25 and 37, have pursued civil engineering at a professional institution, and pass a rigorous examination prior to acceptance.[lxxiv] Lastly, on August 23, 1881 the Navy authorized CEC officers to wear the line officers’ uniform, albeit with light-blue velvet inset between the rank stripes on the sleeves and on the shoulder straps, the latter bearing the letters “CE” in Old English script.[lxxv]

With the CEC’s future in the Navy secure, Sanger could at last step away. He retired from the Navy on October 15, 1881, after 54 years of service as a civilian, civil servant and commissioned officer.[lxxvi] He remained in Washington with his second wife, Lucy Martha Darrell, having remarried following the death of his first wife on March 4, 1877.[lxxvii] The Navy’s first civil engineer died on the morning of February 16, 1890, at age 81, and was interred in Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, Washington, D.C., two days later.[lxxviii] Although Sanger remains a somewhat enigmatic figure, his service as a civil engineer for the U.S. Navy contributed to a tremendous expansion and modernization of the naval shore establishment. He began his career as a civilian for the Board of Navy Commissioners and rose to a commissioned officer with the Bureau of Yards and Docks. One can safely state that the foundation of today’s Civil Engineer Corps firmly rests upon Sanger’s lifetime of service, having transformed a civil engineering apprenticeship into an established branch of the Navy’s staff corps.

William P.S. Sanger Chronology

May 26, 1810: Born, Ward 10, Boston, Massachusetts

1826: Graduates from English High School, Boston, Massachusetts; named Franklin Medal Scholar for meritorious scholarship

March – November 1827: Enters civil engineering apprenticeship under Loammi Baldwin, Boston, Massachusetts

November 1827 – March 1834: Serves as resident engineer for Gosport Navy Yard dry dock construction site, Norfolk, Virginia

May – September 1833: Surveys parts of Norfolk County and Princess Anne County, Virginia, for Board of Public Works

Feb. 20 1834: Marries Martha Webb in Norfolk, Virginia

March 1834 – September 184: Civil engineer for Gosport Navy Yard, Virginia

Jul.8, 1836: Employed by Board of Navy Commissioners as civil engineer; remains civil engineer of Gosport Navy Yard

Late Summer – Fall 1836: Possibly accompanies Loammi Baldwin for surveys in New York and New Jersey

Sept. 15, 1842: Appointed civil engineer for Bureau of Navy Yards and Docks, Washington, D.C.

July – August 1844: Surveys and maps Memphis Navy Yard, Tennessee

November 1844 – January 1845: Surveys and examines harbors at Pensacola, Florida and Portsmouth, New Hampshire regarding construction of dry docks and floating docks

March 1845 – February 1846: Serves as chief engineer for construction of New York Navy Yard dry dock

Early 1852 – Aug. 31, 1852: Travels to California to survey site for Mare Island Navy Yard

August – October 1862: Surveys League Island in the Delaware River near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the harbor of New London, Connecticut, and waters of Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island as site for new navy yard

Mar. 3. 1867: Commissioned as chief civil engineer in U.S. Navy

September 1872 – March 1873: Heads planning board for improvement of League Island Navy Yard, Pennsylvania

September – November 1873: Heads planning board for improvement of Mare Island Navy Yard, California

Jul. 10, 1877: Marries Lucy Martha Darrell, Washington, D.C.

Feb. 24, 1881: Recognized with relative rank of captain in U.S. Navy

Oct. 15, 1881: Retires from U.S. Navy at relative rank of captain

Feb. 16, 1890: Dies at home, 3809 Prospect Avenue, Georgetown, Washington, D.C.

Feb. 18, 1890: Interred at Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, Washington, D.C

[i] The “Navy” part of the title was dropped in July 1862. See Act to Reorganize the Navy Department of the United States, Public Law 134, 37th Cong., 2d sess. (5 July 1862), 510-11.

[ii] “For Sale or to Be Let,” Columbian Centinel (Boston, MA), 26 March 1817, 4; “Married,” Boston Daily Advertiser, 21 April 1817, 2; “Health Commissioners,” Boston Commercial Gazette, 23 May 1822, 2; “Died,” Essex Register (Salem, MA), 9 October 1822, 3; “Notice,” Columbian Centinel, 9 November 1822, 1; “Health Office,” Independent Chronicle and Boston Patriot, 9 August 1823, 4; U.S. Census, 1810: Boston Ward 10, Suffolk, Massachusetts, NARA roll 21, 391; headstone for W.P.S. Sanger, Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, Washington, DC, Chapel Hill section, Lot 533.

[iii] U.S. Census, 1820: Boston Ward 10, Suffolk, Massachusetts, 303; NARA roll M33-53, 151.

[iv] Annals of Congress, 18th Cong., 1st sess., 776-77.

[v] Annals of Congress, 18th Cong., 1st sess., 782; Department of the Navy, Dry Docks, 18th Cong., 2d sess., 1825, Naval Affairs Doc. 252. Baldwin, son of a Revolutionary War colonel, was one of the nation’s preeminent civil engineers in the early nineteenth century. A Massachusetts native, he graduated from Harvard in 1800 and after further study opened a law office in Cambridge, MA in 1804. Law, however, did not suit his interests and Baldwin closed the office in 1807, having instead decided to devote his energies to civil engineering. Following a journey to England to examine various public works, he opened an office in Charlestown, MA and proceeded in 1814 to construct Fort Strong on Noddle’s Island in Boston Harbor. The fort proved a success and thereafter Baldwin’s services found demand in Massachusetts, Virginia, and Pennsylvania for the design and supervision of canals and public works projects. He traveled to Europe in 1824 and spent a year examining public works in France and Belgium, notably the docks at Antwerp.This experience aided Baldwin in regards to plans and estimates for a dock at Charlestown, as communicated to Southard in November 1824. See George L. Vose, A Sketch of The Life and Works of Loammi Baldwin, Civil Engineer, Read Before the Boston Society of Civil Engineers, Sept. 16, 1885 (Boston: Geo. H. Ellis, 141 Franklin St., 1885), 6-15; House Committee on Naval Affairs, Docks for Repairing Ships of War, 19th Cong., 1st sess., 1826, H. Doc. 143, 14-23.

[vi] Cong. Deb. 2605-6 (1826); Edward P. Lull, History of the United States Navy-Yard at Gosport, Virginia (Near Norfolk) (Washington, DC: GPO, 1874), 30; “Selected Summary,” Boston Traveler, 15 September 1826, 2.

[vii] House Committee on Naval Affairs, Dry Docks – Portsmouth, N.H., Charlestown, Mass., &c., 19th Cong., 2d sess., 1827, H. Doc. 125, 5-46.

[viii] Lull, Gosport, 30; “We understand that a commission. . . ,” Pittsfield Sun (MA), 24 May 1827, 1.

[ix] Department of the Navy, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 23d Cong., 2d sess., 1835, S. doc. 63, 2-3.

[x] Vose, Sketch, 28. Vose interviewed Sanger in 1885, then 75 years of age, and reported that Sanger “entered Mr. Baldwin’s office in 1827, and was employed upon the dry docks from that date until their completion. . . .” No other records have been located to confirm or deny this date.

[xi] Palmer C. Ricketts, History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824 – 1934, 3d ed. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1934), 70-81.

[xii] Vose, Sketch, 26.

[xiii] Boston School Committee, Annual Report of the School Committee of the City of Boston, 1875 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1876), 324. The Franklin Medal, named in honor of Benjamin Franklin, was an honorary reward awarded annually in the 19th century “to a number of the most meritorious scholars in the highest class of each public school for boys, above the primary grade. See Boston School Committee, The Association of Franklin Medal Scholars (Boston: Geo. C. Rand and Avery, 1858), 2-12.

[xiv] William Strickland to Loammi Baldwin, 22 July 1827, Loammi Baldwin Papers, Box 1, folder 11, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library, Chicago, IL.

[xv] Vose, Sketch, 17-18.

[xvi] Edwin C. Bearss, Historic Resource Study: Charlestown Navy Yard 1800 – 1842, Boston National Historical Park, Massachusetts (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984), 459-60; Helen W. Davis, Edward M. Hatch, and David G. Wright, “Alexander Parris: Innovator in Naval Facility Architecture,” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Architecture 2, no. 1 (1976): 4-5.

[xvii] Department of the Navy, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 23d Cong., 2d sess., 1835, S. doc. 63, 5.

[xviii] Lull, Gosport, 32.

[xix] Davis, Hatch, and Wright, “Alexander Parris,” 5-6n8; Vose, Sketch, 17-18; Charles B. Stuart, The Naval Drydocks of the United States (New York: Charles B. Norton, 1852), 65. Davis, Hatch, and Wright note that contrary to Stuart, citing Vose, Parris served as Baldwin’s assistant superintendent at both dry dock projects. Sanger, however, traveled with Baldwin as well, having received $102.48 in reimbursement in 1830 “for traveling from Boston to New York with Mr. Baldwin, Engineer, to survey, make plans, &c. and for board while there.” Also listed with Sanger is Benjamin Franklin Perham, another apprentice (age 21) to Baldwin at this time. The autobiography of Calvin Brown, who later served under Sanger as a civil engineer at Norfolk and Mare Island, CA before commissioning as a member of the Civil Engineer Corps, writes that Parris “had been superintendent of the Charlestown dry dock and also of that of Norfolk, Virginia, under the direction of Colonel Loammi Baldwin, the engineer. . . .” Brown later notes how Sanger “was professionally educated in the service of Colonel Loammi Baldwin and was his assistant in the building of the dry dock at that Norfolk Navy Yard.” See Department of the Navy, Pay, &c. of Naval Officers and Agents, 21st Cong., 1st sess., 1830, H. Doc. 121, 49; Vose, Sketch, 26; Calvin Brown, Autobiography (California: 1890 – 1895?), 112, 171, original in possession of U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Naval Base Ventura County, Port Hueneme, CA (USNCBM).

[xx] Lull, Gosport, 31-32.

[xxi] Voss, Sketch, 18.

[xxii] Lull, Gosport, 36. The Charlestown dry dock, by comparison, cost $677,089.78. See Schedule of Papers Accompanying Report of the Secretary of the Navy to President of the United States, 24th Cong., 2d sess., 1836, S. Doc. 1/8, 502.

[xxiii] “Report of William P.S. Sanger, Civil Engineer, on the Survey and Plan of the Country Between Great Bridge and North Landing,” in Virginia Board of Public Works, Seventeenth Annual Report of the President and Directors of the Board of Public Works, to the General Assembly of Virginia, January 17, 1833 (Richmond, VA: Samuel Shepherd and Co., 1833), 222-23.

[xxiv] William P.S. Sanger to Loammi Baldwin, 1 May 1834, Personal Papers collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[xxv] Lull, Gosport, 38-39.

[xxvi] No definitive, primary documentation has been located to verify this information. Sanger’s headstone lists Martha as his wife, but without any indication as to the date of marriage. The Bready Family Tree on Ancestry.com lists this date of marriage but without documentation. In the 1840 U.S. Census, Sanger’s household lists two free white women from ages 20 to 29. As Martha was born in 1813, this would make her one of the two (the other remains unknown, but may have been a midwife). See Bready Family Tree, “William P.S. Sanger,” AncestryLibrary.com (accessed 3 February 2014); U.S. Census, 1840: Portsmouth, Norfolk, Virginia, roll 570, 126.

[xxvii] “Chiefs of Bureau of Yards and Docks,” Bureau of Yards and Docks News – Memorandum 4, no. 80 (1 July 1933): 1390

[xxviii] House Committee on Naval Affairs, Navy Yards – Great Barn Island, Perth Amboy, &c., 24th Cong., 2d sess., 1836, 1-2; Office Secretary of the Senate, Report in Compliance with the “Act to Authorize the Appointment of Additional Paymasters, and for other Purposes,” approved July 4, 1836,” 24th Cong., 1st sess., 1836, 6.

[xxix] Lull, Gosport, 38-39. The 1840 U.S. Census also lists Sanger as living in Norfolk and owning two female slaves, possibly as cooks or housekeepers. See U.S. Census, 1840: Portsmouth, Norfolk, Virginia, roll 570, 126.

[xxx] House Committee on Naval Affairs, Reorganization of the Navy Department, 26th Cong., 1st sess., 1839, H. Doc. 39, 1-4.

[xxxi] Act to Reorganize the Navy Department of the United States, Public Law 286, 27th Cong., 2d sess., (31 August 1842), 579-81.

[xxxii] Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Navy of the United States including Officers of the Marine Corps, Corrected from Authentic Sources, to the 15th September 1842 (Washington, DC: Alexander and Barnard, printers, 1842), iii; excerpts from letters of William P.S. Sanger as transcribed by Helen W. Fairbanks from originals in files of BuDocks, National Archives, unlabeled folder, Record Group (RG) 4, Series III, Box 1, USNCBM; Department of the Navy, Schedule of Papers Accompanying the Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 27th Cong., 3d sess., 1842, H. Doc. 29, 562.

[xxxiii] Senate Committee on Naval Affairs, Report of Secretary of the Navy on Plans and Estimates for Construction of a Permanent Wharf and Dry Dock at Pensacola, 29th Cong., 1st sess., 1844, S. Doc. 134, 1-21; Department of the Navy, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 28th Cong., 1st sess., 1844, S. Doc. 1/6, 522-23; House Committee on Naval Affairs, William P.S. Sanger and George F. De La Roche, 29th Cong., 1st sess., 1846, H. Rep. 367, 1; House Committee on Naval Affairs, A Report of Officers and Engineers Relative to the Properties and Advantages of a Dry Dock, &c., 28th Cong., 2d sess., 1845, H. Doc. 163, 1-79; House of Representatives, Dry Dock at Brooklyn, and Land Between Naval Hospital and Navy Yard, Brooklyn, 30th Cong., 1st sess., 1848, Mis. Doc. 71, 1-8; Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 19 November 1844; report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 14 November 1846; report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 4 November 1848; report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 17 October 1849, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (1 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 2, USNCBM; Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 12 October 1850, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (2 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[xxxiv] Charles B. Stuart, The Naval Dry Docks of the United States (New York: Charles B. Norton, 1852), 9-15, 119.

[xxxv] “History of the Civil Engineer Corps, United States Navy,” undated, 2, folder labeled “RG3 – General, History of the Civil Engineer Corps, United States Navy; Publication, [1950s],” RG3, Series 1, Box 6, USNCBM; Act Making Appropriations for the Naval Service for 1851, Public Law 80, 31st Cong., 1st sess. (28 September 1850), 513-17.

[xxxvi] Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 16 October 1851, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (2 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[xxxvii] “Naval,” Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, DC), 2 September 1852, 3; Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 14 October 1852, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (2 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM. As fate would have it, the same day Sanger and the commission arrived back in Washington, DC, Congress authorized and directed the Secretary of the Navy to select the site for a navy yard and naval depot in and /or around San Francisco Bay. See Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 31 October 1853, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (2 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[xxxviii] Senate, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 33d Cong., 1st sess., 1853, S. Ex. Doc. 1/10, 304; Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 1 November 1854, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (2 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[xxxix] Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 12 October 1855, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (2 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[xl] Stanley K. Adamiak, “A Naval Depot and Dockyard on the Western Waters: The Rise and Fall of the Memphis Naval Yard, 1844 – 1854,” International Journal of Naval History, 1, no. 1 (April 2002): 1-12.

[xli] Senate, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 33d Cong., 1st sess., 1853, Ex. Doc. 1/10, 306.

[xlii] Senate, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 34th Cong., 1st sess., 1855, Ex. Doc. 1, 20-21.

[xliii] This statement is a condensed summary from the Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 1 December 1856; 15 October 1857; 22 November 1858; 1 October 1859; and 22 November 1860, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1842 to 1860 (3 of 3),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[xliv] The exact circumstances as to how Sanger was able to hire additional civil engineers is not entirely known, although it can safely be stated that necessity for supervision of repairs and various projects, combined with budgetary allowances justified the expansion of Navy civilian civil engineers. See Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the Navy of the United States, including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, for the Year 1861 (Washington, DC: George W. Bowman, 1861), 98-101.

[xlv] House of Representatives, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 35th Cong, 2d sess., 1858, Ex. Doc. 2, 193-94. Sanger may have drafted the civil engineer portion of the code in 1857, but this is not entirely clear. See also “History of the Civil Engineer Corps, United States Navy,” undated, 2, folder labeled “RG3 – General, History of the Civil Engineer Corps, United States Navy; Publication, [1950s],” RG3, Series 1, Box 6, USNCBM.

[xlvi] Edwin C. Bearss, “Civil War Operations in and Around Pensacola,” Florida Historical Quarterly 36 no. 2 (October 1857): 132-33. The dock itself was later scuttled by the Confederates. See Edwin C. Bearss, “Civil War Operations in and around Pensacola, Part II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 39, no. 3 (January 1961): 248-49.

[xlvii] The loss of the yard at Norfolk with so much usable war material captured would be deemed the “Gosport Affair,” as federal officials sought to determine how the yard’s capture could have been so badly bungled. Many of the captured guns would be put into use across the Confederacy. See John Sherman Long, “The Gosport Affair, 1861,” Journal of Southern History 23, no. 2 (May 1957): 155-72; William N. Still, Jr., “Facilities for the Construction of War Vessels in the Confederacy,” Journal of Southern History 31, no. 3 (August 1965): 299-300; Lull, Gosport, 44-59; Senate Committee on Printing, Circumstances Attending Surrender of Navy Yard at Pensacola, and Destruction of Property at Navy Yard at Norfolk and at Armory at Harper’s Ferry, 37th Cong., 2d sess., 1862, S. Rep. 37, 1-21.

[xlviii] Lull, Gosport, 60-61; Edwin C. Bearss, “Civil War Operations in and Around Pensacola, Part III,” Florida Historical Quarterly 39, no. 4 (April 1961): 338-39, 349-52.

[xlix] Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 4 November 1862, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1861 to 1880 (1 of 4),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[l] “The Secretary of the Navy has appointed…,” Harford Daily Courant (CT), 15 August 1862, 2; Kenneth W. Munden and Henry P. Beers, Guide to Federal Archives Relating to the Civil War (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1962), 479. During this time away from Washington, William J. Keeler represented Sanger as the resident civil engineer at BuDocks. Keeler is listed in the Navy’s Register of Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers from 1862 to January 1863, with date of appointment listed as 9 July 1862. See Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to September 1, 1862 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1862), 9; Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to January 1, 1863 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1863), 9.

[li] House of Representatives, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 37th Cong., 3d sess., 1862, Ex. Doc. 1, 33.

[lii] House of Representatives, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 37th Cong., 3d sess., 1862, Ex. Doc. 1, 33-35; Senate Committee on Naval Affairs, Majority and Minority Reports of Board of Officers to Accept Title to League Island, Delaware River, for Naval Purposes, 37th Cong., 3d sess., 1862, Ex. Doc. 9, 1-29. It must be noted that the city of Philadelphia offered the island to the Navy and Congress authorized the Secretary of the Navy to accept the island if approved by a board of officers on 15 July 1862. The factor of acquiring the island versus purchasing tracts of land in New London factored considerably into Welles’ decision to choose the minority opinion. See also Secretary of the Navy, Reports of the Secretary of the Navy, and the Commission by him Appointed, on the Proposed New Iron Navy Yard at League Island (Philadelphia, PA: Collins, 1863).

[liii] Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 15 October 1864, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1861 to 1880 (2 of 4),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[liv] Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 12 October 1865, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1861 to 1880 (2 of 4),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[lv] House of Representatives, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 39th Cong., 1st sess., 1865, Ex. Doc. 1, xvii.

[lvi] Ibid., xvii-xviii.

[lvii] House of Representatives, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 39th Cong., 2d sess., 1866, Ex. Doc. 1, 24-29.

[lviii] An Act to Establish the Offices of Civil Engineer and of Master Mechanics and Master Laborer in Navy Yards of the United States, HR 1186, 39th Cong., 2d sess. (20 February 1867), 1-2.

[lix] Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 2d sess. 1401-02 (1867).

[lx] Naval Appropriation Act of 1868, Public Law 172, 39th Cong., 2d sess. (2 March 1867), 490.

[lxi] Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to January 1, 1880 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1880), 77.

[lxii] Department of the Navy, Register of the Commissioned, Warrant, and Volunteer Officers of the Navy of the United States, including Officers of the Marine Corps and Others, to January 1, 1873 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1873), 73.

[lxiii] Naval Appropriation Act of 1871, Public Law 295, 41st Cong., 2d sess. (15 July 1870), 331-32.

[lxiv] Naval Appropriation Act of 1872, Public Law 117, 41st Cong., 3d sess. (3 March 1871), 536-37. Relative rank was a practice from 1871 to 1899 for the early CEC and other Navy staff corps officers whereby a rank relative to that for an officer’s experience, competency, and service was recognized commiserate with an officer of the line, but it was not a permanent rank. A civil engineer held the actual rank and address of “Civil Engineer,” even if possessing the relative rank of lieutenant or commander.

[lxv] Department of the Navy, Bureau of Yards and Docks, Report of the Board of Civil Engineers Appointed to Prepare a Plan for the Improvement of the Navy-Yard at League Island, Pennsylvania (Washington, DC: GPO, 1873), 3.

[lxvi] An Act to Authorize the Secretary of the Navy to Accept League Island, Public Law 46, 39th Cong., 2d sess. (18 February 1867), 396.

[lxvii] Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 27 October 1871; 1 November 1872, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1861 to 1880 (3 of 4),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM; Department of the Navy, Bureau of Yards and Docks, Report of the Board of Civil Engineers Appointed to Prepare a Plan for the Improvement of the Navy-Yard at League Island, Pennsylvania (Washington, DC: GPO, 1873), 6-16.

[lxviii] Department of the Navy, Bureau of Yards and Docks, Report of the Board of Civil Engineers, Appointed to Prepare a Plan for the Improvement of the Navy-Yard at Mare Island, California (Washington, DC: GPO, 1873), 3-22.

[lxix] Naval Appropriation Act of 1868, Public Law 172, 39th Cong., 2d sess. (2 March 1867), 489; House of Representatives, Report of the Secretary of the Navy, 41st Cong., 2d sess., 1869, Ex. Doc. 1/4, 19; Report of the Chief, Bureau of Yards and Docks to the Secretary of the Navy, 25 October 1870, folder labeled “Reports: Chiefs Annual Report to SecNav 1861 to 1880 (3 of 4),” RG 16, Series 3, Box 3, USNCBM.

[lxx] Department of the Navy, Bureau of Yards and Docks, Report of the Board of Civil Engineers Appointed to Prepare a Plan for the Improvement of the Naval Station at New London, Connecticut, June 17, 1875 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1875), 3.

[lxxi] See A Bill Fixing the Relative Rank of Civil Engineers in the Navy, HR 4299, 43d Cong., 2d sess. (11 January 1875), 1; A Bill Fixing the Pay and Rank of Civil Engineers in the Navy, S 1074, 43d Cong., 2d sess. (5 January 1875), 1; A Bill Fixing the Rank and Pay of Civil Engineers in the Navy, HR 1164, 44th Cong., 1st sess. (17 January 1876), 1; A Bill Fixing the Relative Rank of Civil Engineers in the United States Navy, HR 5672, 45th Cong., 3d sess. (16 December 1878), 1; A Bill Fixing the Rank of Civil Engineers in the United States Navy, HR 2216, 45th Cong., 2d sess. (14 January 1878), 1; A Bill to Reduce the Number and Fix the Relative Rank of Civil Engineers in the Navy, HR 5917, 45th Cong., 3d sess. (20 January 1879), 1-2; A Bill to Reduce the Number and Fix the Relative Rank of the Civil Engineers of the Navy, S 1730, 45th Cong., 3d sess. (29 January 1879), 1-2.

[lxxii] Department of the Navy, General Order No. 263, 24 February 1881. The order fixed the size of the CEC at ten officers, one with relative rank of captain, two with the relative rank of commander, three with relative rank of lieutenant commander, and four with the relative rank of lieutenant.

[lxxiii] Department of the Navy, General Order No. 274, 1 November 1881. The general order republishes the Attorney General’s reply to an inquiry from Navy Civil Engineer Benjamin F. Chandler, dated 17 June 1881.

[lxxiv] Department of the Navy, “Regulations Governing the Appointment of Civil Engineers in the U.S. Navy,” 14 July 1881.

[lxxv] Lewis B. Combs, “Civil Engineer Corps, U.S. Navy,” The Military Engineer 35, no. 209 (March 1943): 106-07; James C. Tily, “The U.S. Navy CEC Device,” U.S. Navy Civil Engineer Corps Bulletin 13, no. 1 (January 1959): 3.

[lxxvi] Cong. Rec., 47th Cong., 1st sess., 1882, 13, pt. 6: 6289. Sanger was joined in retirement with Benjamin F. Chandler, Calvin Brown, and Norman Stratton, thereby opening up four new slots in the CEC. See “Civil Engineers in the Navy,” Engineering News, 3 December 1881, 487.

[lxxvii] Bready Family Tree, “William P.S. Sanger,” AncestryLibrary.com (accessed 3 February 2014); U.S. Census, 1880: Georgetown, Washington, District of Columbia, roll 121, family history film 1254121, 233D. Lucy Martha Darrell Sanger would remarry in 1892 to Conrad J. Cooper of Philadelphia. She died on 2 September 1909. See “Marriage Licenses,” Washington Post, 28 September 1892, 7; “Died,” Washington Post, 4 September 1909, 2.

[lxxviii] “Death of a Former Naval Officer,” Washington Post, 17 February 1890, 2.